Book Review by Denise McCluggage

Let’s say I have rescued some wizened magical elf from a disaster, like an excruciating death, or a hangnail or watching teen-age TV sitcoms. In his gratitude he has granted me a wish. My wish is that every driver in the country would read and apply the lessons in a new book about driving.

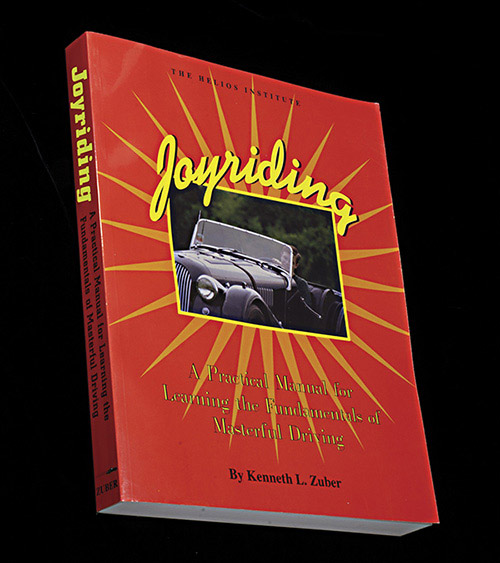

With the granting of that wish would come a nation of skillful, attentive and safe drivers who not only are masters of technique, but who actually enjoy the process. The book is called “Joyriding: A Practical Manual for Learning the Fundamentals of Masterful Driving,” by Kenneth L. Zuber, of Homewood, Ill. Mr. Zuber is a teacher of driving and his manual is meant to instruct. (It does that extremely well.)

But more than just instructing, Mr. Zuber’s book is meant to instill in the student driver – and we are forever students – something of what he feels about driving.

“Do not rush and make every drive a torture test. Look at your driving as a lifelong body of work of which to be proud. Drive according to conditions. Drive according to moods. Expect variety. Expect different challenges and rewards. Try to make each and every drive a chapter in your personal history of driving enjoyment, accomplishment, ever increasing mastery, and satisfaction in personal growth!”

That’s what Mr. Zuber means by “joyriding.” That resonates so completely with my own approach to driving that it is eerie. And, oddly, it is almost counter to how driving is traditionally taught, and treated, by the schools and government and insurance bureaucracies. Driving in their publications and pronouncements seems to be something that has to be done as if it were some arduous process to prevent gum disease. If driving is fun then you must be doing something illegal. Stop that smiling; quell that exuberance.

If driving entails some exuberance, it is not free-form, like making figure eights in rubber on the highway, or celebrating a team’s success by lobbing bricks through storefronts. There are rules and processes. There are responsibilities. “Driving,” Mr. Zuber says “means controlling.” The pleasure in driving ultimately stems from control. “Control of a car means grace, balance, safety and efficiency.”

In no book have I read such detailed and useful information on the minutiae of driving. How and where to look, how to back up, how to parallel park, how to read traffic, how to adjust the mirrors, how to drive on interstates, how to correct for skids, how to merge, how to change a tire, how to use a clutch smoothly, how to read a map, how to drive.

There’s no end to it. And this telephone-directory size book is chock-a-block with straightforward, direct, clear instructions and information on every aspect of driving you can imagine, and some you can’t. This is far from the usual stuff presented in the usual manner. Mr. Zuber has carefully thought through every point he wants to make and often comes up with a unique approach that creates a quick arc of illumination. You thump the book and shout, “Exactly.”

Mr. Zuber does not rely on his direct prose alone. The book is loaded with illustrations. Diagrams of clarity and detail show, for instance, where to aim your eyes in certain intersections and what to look for, where to hold the wheel, how to make several varieties of U-turns, etc.

Photographs demonstrate such matters as the importance of point of view, the perils in blind areas, and many other matters, but the pictures are joys in themselves. A variety of cars are used from race cars to interesting vintage cars – a Chrysler Town & Country woody, a Nash Metropolitan, a DeLorean, a Rolls-Royce, to name a few. Also some fine old trucks. And check the Ferrari used to illustrate parallel parking.

Are there faults in this book? Yes. An index, which is lacking, would be inordinately useful. This is a reference book that will be returned to time and again. (Perhaps in future editions.) And, too, the title “Joyriding” has a downside. Yes, it should mean what Mr. Zuber makes it mean – delight in driving well, but it also means taking an unauthorized spin in someone else’s car. Unfortunate.

Book Review from Driver/Education – Volume 12-Issue 1-April 2002

A story of two books –

Just about everybody who drives has ideas about driving and how it should be done. This is particularly true of driver training professionals. Every now and again, one of them puts ideas to paper and produces something that can be presented, either to their peers or to drivers who want to learn. Driver/Education has always been aimed at facilitating this process. In this issue we present two new books, very different in approach, but both a labor of love by their authors.

Ken Zuber is based in Homewood, Illinois. He’s been involved in driver education since 1969, is a car enthusiast, raced sports cars back in the ’70s, and loves driving.

Trevor Hobbs is based in New South Wales, Australia. He’s a former police driving instructor, road safety lecturer, driver examiner, and recipient of a master driver award. His book is about 100 pages, including space for note taking.

While Zuber’s book is a comprehensive, in-depth textbook on the driving task, Hobbs’s book, Driving from L to P, is more of an in-car guide, an outline that maps out the essential ingredients of lessons.

Each author has taken the time and trouble to put ideas and thoughts about driving into words and on to publishable pages. Their efforts are worthy of attention.

Over the years there have been many textbooks on driving, many of them very expensive to produce. However, it’s always a weakness of driving textbooks, and driver education programs in general, that there has never been a real in-depth analysis of the nuts and bolts of driving. It’s not enough to systematically map out the parts of the task in logical sequence, there has to be meat on the bones. The greatest source of that meat, the professionals who do the everyday job of instructing drivers, have been very much under-represented in the production of training programs and materials. This is unfortunate, because, as Ken Zuber amply demonstrates, there are some great ideas out there.

Language and ideas

It’s unlikely that fellow professionals out there would agree with everything either of these authors writes, and that’s inevitable, given the nature of driving.

However, any new way of looking at driving and instruction should be of interest to professionals, and Zuber’s book in particular, is rich in ideas and descriptions. His enthusiasm for driving comes across in his introduction. He starts with interesting stories from the annals of race driving, and then moves along into a great description of what street driving is all about.

“Driving means controlling,” he writes. “The feeling of control is a basic human need. When we do not feel at least some control, we are afraid …control is why the driver is respected.” Control, he goes on to explain, means grace, balance, safety, and efficiency.

For Zuber, driving is a passion, an adventure. He tries to convey this passion to his readers. His major criticism of driver education as we know it in North America is that it gets away from that.

“Driver education must stop its doomed efforts to teach students that their longings for freedom, control and heroism are wrong. Instead, driver education must use these passions as the strong foundations for learning to drive well.”

These are sentiments that will have a familiar ring to regular reader of Driver/Education newsletter. “Nobody learns to drive to be safe,” Zuber argues. They learn because they want to drive.

Insights and experiences

Anyone who is knowledgeable about the human psyche and about cars and driving is bound to have those “aha” experiences while teaching. Zuber has obviously had lots of them. His book is peppered with valuable insights and is thorough in its coverage of all aspects of driving.

It aims at being a textbook for novice drivers but it would be a good addition to the shelves of any professionals who want the perspectives of a thoughtful peer as a means of providing depth to their own understanding.

Trevor Hobbs’s book is written from an Australian standpoint. It will seem very rudimentary to anyone familiar with the variety of textbooks available in North America, but it’s obviously written with behind-the-wheel lessons, and the need for note taking, in mind.

Book Review from National Motorists Association Foundation News July/August 2002

If your’re a parent, uncle, grandmother, or just an older friend of a young person who is about to learn how to drive, I’d like to suggest a great and lasting gift. Give them a copy of “Joyriding: A Practical Manual for Learning the Fundamentals of Masterful Driving.”

This is a book that starts out with the premise that driving is just about the greatest thing a human being can do. Driving is a right of passage. Driving is a skill to be honed and refined into a fine art. And yes, driving is a responsibility with consequences. But more than anything else, driving is and should be fun!

The author, Ken Zuber, extols the virtues of driving as an end all to itself. He acknowledges the importance of “safety,” but correctly points out that safety is a byproduct of being a good and skilled driver.

“Joyriding” is not just a commercial version of a 40-page Department of Motor Vehicles drivers’ manual that explains the difference between stop signs and yield signs, all the while harping about the dangers of driving. “Joyriding” is a 400-page book that covers just about every aspect of practical car handling techniques, driving tactics, and strategies that result in masterful and enjoyable driving.

If you want to get a new driver off on the right foot as they begin their driving careers, you couldn’t do better than to give them this book – and insist that they read it. It won’t take much persuasion. The book talks to them about something they really want to learn, and it presents the information as if it’s coming from someone who shares their excitement in reaching this wonderful stage of life.